About

This page explains how to mount filesystems, either from partitions on your system’s hard disks or from other file servers.

Introduction to filesystems

On a Unix system, all files exist in a tree or directories under the root / directory. Drive letters used by other operating systems (like Windows) to identify different hard disks or network drives do not exist. Instead, different hard disks, CD-ROMs, floppy disks and network drives are attached to the directory tree at different places, called mount points. For example, /home may be a mount point for a different hard disk on your system, and /usr/local may be the mount point for files that are shared from another server. The root directory is also a mount point, almost always for a partition on a hard disk in your machine. The set of files that is actually mounted at a mount point is called a filesystem.

All operating systems divide each hard disk up into partitions, each of which can be a different size. Each filesystem is normally stored on one partition of one disk, so it is possible to have multiple filesystems of different types on the same hard disk - one for Linux and one for Windows for example. If you have multiple hard disks in your system, you will normally need to mount at least one filesystem from each in order to make use of them.

Unix systems support many different kinds of filesystem, some for files stored on local hard disks and some for files on networked file servers. On Linux, the filesystems on your hard disks will probably be in ext3 or ext4 format. Many other local filesystem types exist, such as iso-9660 for CD-ROMs, vfat for Windows partitions, and xfs and reiserfs for high performance file access. Every local filesystem type uses a different format for storing data on disk, so if a partition has been formatted as a filesystem of a particular type, then it must be mounted as that type.

There are also filesystem types for different methods of accessing file servers across a network. If the file server is running Unix, then an nfs filesystem is usually mounted to access its files. However, it is running Windows then an smbfs filesystem must be used instead. These different filesystem types correspond to different network protocols for accessing files on another system.

Other special filesystem types contain files that do not actually exist on any disk or file server. For example, a proc filesystem contains files that contain information about currently running processes. Different Unix variants have different types of special filesystems, most of which are automatically mounted by the operating system and do not need to be configured.

No explanation of filesystems can be complete without also covering virtual memory. Often a Unix system will be running processes that take up more memory than is actually installed. This is made possible by the operating system automatically moving some of those processes out of real memory and into virtual memory, which is stored in a file or local hard disk. Because filesystems and virtual memory are both stored on disk and can be mounted and un-mounted, the Disk and Network Filesystems Webmin module also manages with virtual memory.

Depending on your operating system, the file /etc/fstab or /etc/vfstab contains a list of filesystems that are known to your system and mounted at boot time. It is also possible for a filesystem to be

temporarily mounted using the mount command without being stored in the fstab file. Webmin directly modifies this file to manage filesystems that are mounted at boot time, and calls the mount and unmount commands to immediately activate and de-activate filesystems.

The Disk and Network Filesystems module

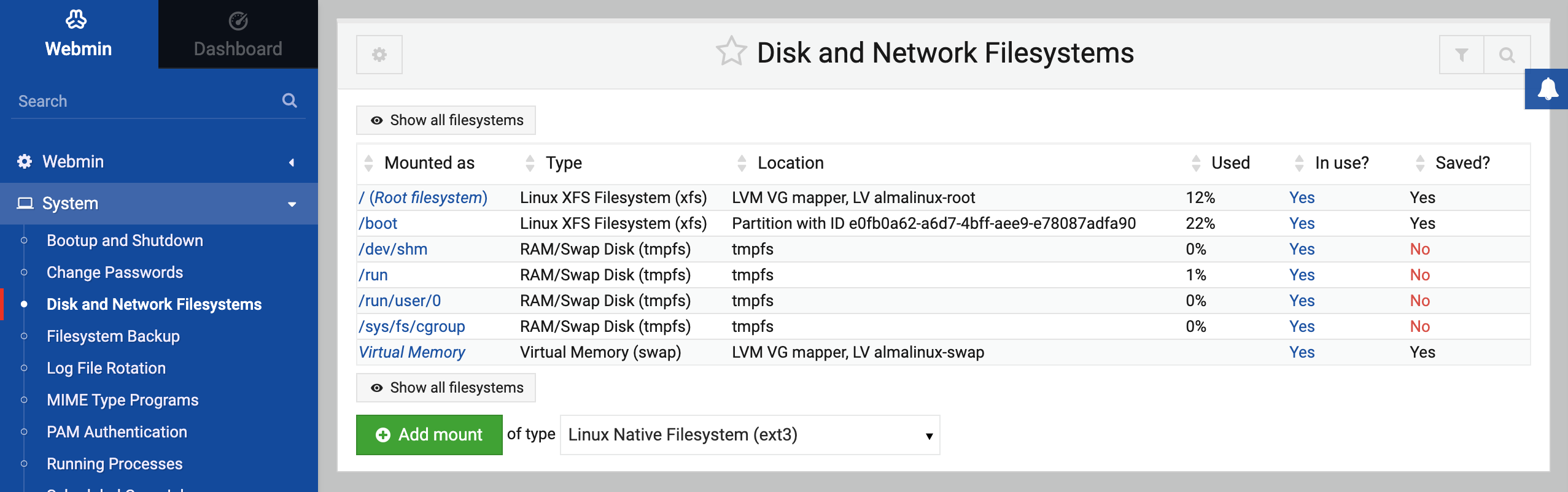

The Disks and Network Filesystems module is found under the System category, and allows you to configure which filesystems are mounted on your computer, where they are mounted from and what options they have set. The main page of the module (shown below) lists all the filesystems that are currently mounted or available to be mounted.

For each filesystem, the following information is displayed:

Mounted As

The mount point directory for this filesystem, or the message Virtual Memory.

Type

A description of the filesystem type, followed by the actual short type name.

Location

This disk-device, partition, LVM-volume, fileserver or other location from which this filesystem was mounted. For

nfsmounts, this column will be in the form servername:remotedirectory, while for mounts it will be like \\servername\sharename.Used

Percentage of filesystem in use

In use?

Yes or No, depending on whether the filesystem is currently mounted. For most filesystems, you can click on this field to mount or un-mount immediately.

Saved?

Yes or No, depending on whether the filesystem is recorded permanently so that it would be mounted at boot time.

Mounting an NFS network filesystem

Before you can mount a filesystem from another Unix server, that server must have been configured to export the directory that you want to mount using NFS.

Assuming the directory that you want to mount has been exported properly, you can follow these steps to mount it on your system:

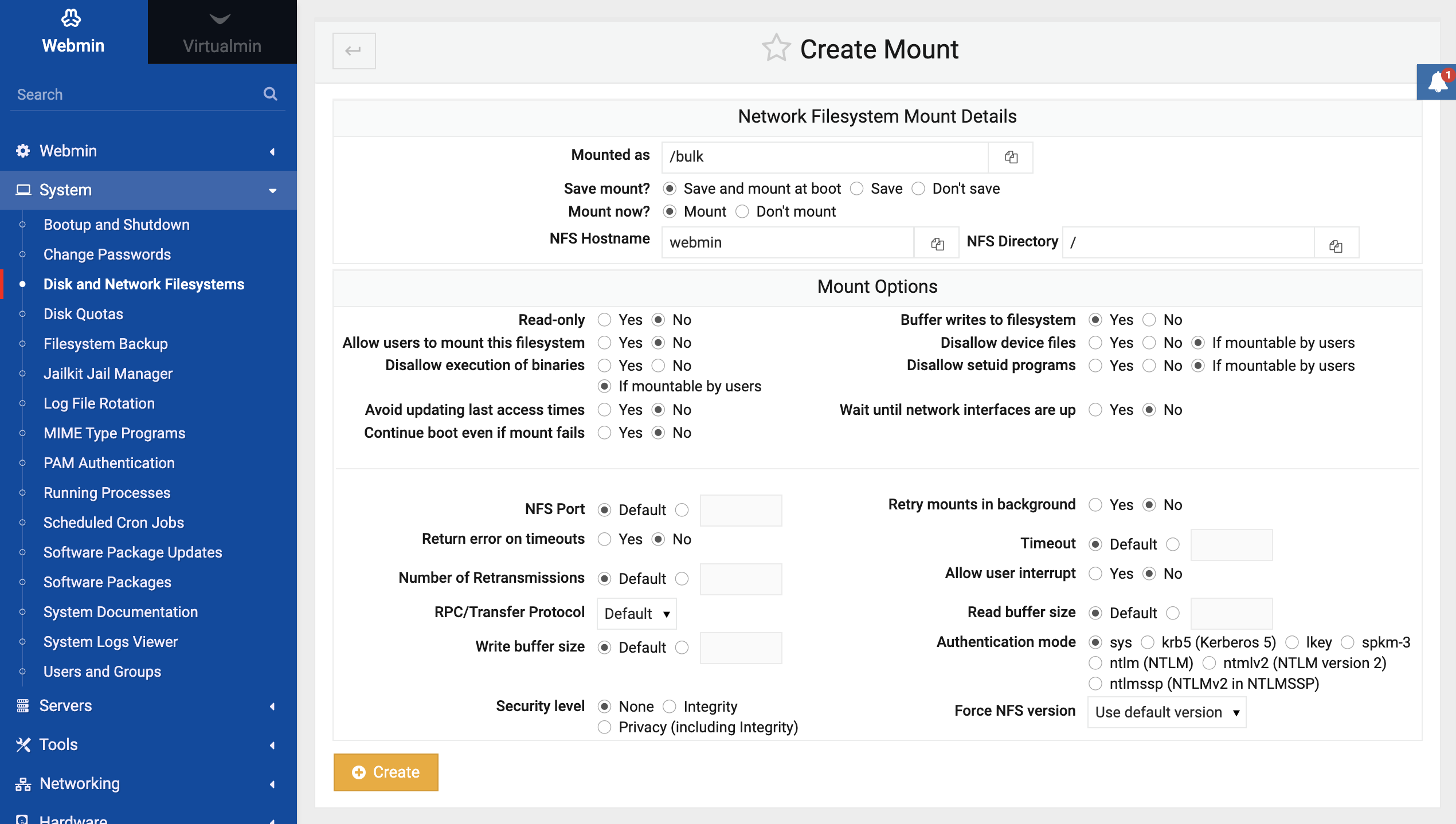

- On the main page of the Disk and Network Filesystems module, select Network Filesystem from the drop-down box of filesystem types, and click the Add mount button. A form will appear as shown below.

- In the Mounted As field, enter the directory on which you want the filesystem to be mounted. The directory should be either non-existent or empty, as any files that it currently contains will be hidden once the filesystem is mounted.

- If you want the filesystem to be mounted at boot time, select Save and mount at boot for the Save Mount option. If you want it to be permanently recorded but not mounted at boot, select Save. Otherwise, select Don’t save if this is to be only a temporary mount.

- For the Mount now? option, select Mount if you want the filesystem to be mounted immediately, or Don’t mount if you just want it to be recorded for future mounting at boot time. It makes no sense to set the Save and mount option to Don’t save and the Mount now? option to Don’t mount, as nothing will be done!

- In the NFS Hostname field, enter the name or IP address of the fileserver that is exporting the directory that you want to mount. You can also click on the button next to the field to pop up a list of NFS servers on your local network.

- In the NFS Directory field, enter the exported directory on the fileserver. If you have already entered the NFS server’s hostname, clicking on the button next to the field will pop up a list of directories that the server has exported.

- Change any of the options in the bottom section of the form that you want to enable. Some of the most useful are:

Read-only?

If set to Yes, files on this filesystem cannot be modified, renamed or deleted.

Retry mounts in background?

Normally, when an NFS filesystem is mounted at boot time your system will try forever to contact the fileserver if it is down or unreachable, which can prevent the boot process from completing properly. Setting this option to Yes will prevent this problem by having the mount retried in the background if it takes too long.

Return error on timeouts?

The normal behavior of the NFS filesystem in the face of a fileserver failure is to keep trying to read or write the requested until the server comes back up again and the operating succeeds. However, this means that if the fileserver goes down for a long period of time, any attempt to access files mounted from the server will get stuck. Setting this option to Yes changes this behavior so that your system will eventually give up on operations that take too long.

- To mount and/or record the filesystem, click the Create button at the bottom of the page. If all goes well, you will be returned to the filesystems list. Otherwise, an error will be displayed explaining what went wrong.

Once the NFS filesystem has been successfully mounted, all users and programs on your system will be able to access files on the fileserver under the mount point directory. Because the NFS protocol supports Unix file permissions and file ownership information, if users can login to both your system and the remote fileserver, any files that they own on one machine should be owned on the other. However, this depends on every user having the same user ID on both servers. If this is not the case, you may end up in a situation in which user jcameron owns a file on the fileserver, but when it is mounted and accessed on your system the file appears to be owned by user fred.

The best solution to this problem is to make sure that user IDs are in sync across all servers that share files using NFS. The best ways to do that are using NIS as explained in NIS Client and Server, LDAP as covered in LDAP Client and LDAP Users and Groups or Webmin’s own Cluster Users and Groups module.

Mounting an CIFS filesystem

smbfs (Samba File System) or cifs (common internet file system) is the protocol used by Windows systems to share files with each other. If you have files on a Windows system that you want to access on your Linux system, you must first share the directory and assign it a share name using the Windows user interface.

Once that is done, follow these steps to mount the share on your Unix system :

- On the main page of the Disk and Network Filesystems module, select Common Internet File System from the drop-down box of filesystem types, and click the Add mount button. A form will appear as shown below.

- In the Mounted As field, enter the directory on which you want the filesystem to be mounted. The directory should be either non-existent or empty, as any files that it currently contains will be hidden once the filesystem is mounted.

- If you want the filesystem to be mounted at boot time, select Save and mount at boot for the Save Mount option. If you want it to be permanently recorded but not mounted at boot, select Save. Otherwise, select Don’t save if this is to be only a temporary mount.

- For the Mount now? option, select Mount if you want the filesystem to be mounted immediately, or Don’t mount if you just want it to be recorded for future mounting at boot time.

- In the Server Name field, enter the hostname or IP address of the Windows server. The button next to the field will pop up a list of Windows servers on your network, requested from the domain or workgroup master set in the module configuration.

- In the Share Name field, enter the name of the share. This will be something like movies, not the full path on the Windows server like

c:\files\movies. If you have entered the server name, clicking on the button next to the field will pop up a list of available shares. - If the Windows server requires a username and password to access the file share, fill in the Login Name and Login Password fields. If no authentication is needed, these fields can be left blank.

- Because Windows networking has no concept of Unix users, when the filesystem is mounted all files from the fileserver will be owned by a single Unix user and group. By default that user is root, but you can change this by filling in the User files are owned by and Group files are owned by fields.

- Click the Create button at the bottom of the page to mount and/or record the filesystem. If all goes well, you will be returned to the filesystems list. Otherwise, an error will be displayed explaining what went wrong.

Windows networking filesystems can also be exported by Unix servers using Samba, as explained in Samba Windows File Sharing. This means that you could share files between two Unix servers using the Windows file sharing protocol CIFS. However, as you might guess this is not usually a good idea as file permissions and ownership information will not be available on the mounting server.

Mounting a local ext3 or ext4 hard disk filesystem

Before you can mount a new filesystem from a local hard disk, a partition must have been prepared and formatted with the corrected filesystem type. If you have a choice, ext4 (called the New Linux Native Filesystem) should be used instead of ext3 (Linux Native Filesystem) because its support for journaling. See the section on A comparison of filesystem types for more details on the advantages of ext4.

To mount your local filesystem, follow these steps :

- On the main page of the Disk and Network Filesystems module, select Linux Native Filesystem or New Linux Native Filesystem from the drop-down box of filesystem types, and click the Add mount button. A form will appear for entering the mount point, source and options.

- In the Mounted As field, enter the directory on which you want the filesystem to be mounted. The directory should be either non-existent or empty, as any files that it currently contains will be hidden once the filesystem is mounted.

- If you want the filesystem to be mounted at boot time, select Save and mount at boot for the Save Mount option. If you want it to be permanently recorded but not mounted at boot, select Save. Otherwise, select Don’t save if this is to be only a temporary mount.

- For the Mount now? option, select Mount if you want the filesystem to be mounted immediately, or Don’t mount if you just want it to be recorded for future mounting at boot time.

- If the Check filesystem at boot? option exists, it controls whether the filesystem is validated with the fsck command at boot time before mounting. If your system crashes or loses power, any

ext3or ufs filesystems that were mounted at the time will need to be checked before they can be mounted. It is generally best to set this option to Check second. - For the Linux Native Filesystem field, click on the Disk option and select the partition which has been formatted for your new filesystem. All IDE and SCSI disks will appear in the menu. If any of the partitions on your system are labeled, you can mount one by selecting the Partition labeled option and choosing the one you want. If your system has any RAID devices configured, you can select the RAID device option and choose the one you want to mount from the menu. If you are using LVM, a list of all available logical volumes will appear next to the LVM logical volume option for you to select from. Alternately, you can click on the Other device option and enter the path to the device file for your filesystem, like

/dev/hda2. - Change any of the options in the bottom section of the form that you want to enable. Some of the most useful are :

Read-only?

If set to Yes, files on this filesystem cannot be modified, renamed or deleted.

Use quotas?

If you want to enforce disk quotas on this filesystem, you must enable this option. Most filesystem types will give you the choice of user quotas, group quotas or both. To complete the process of activating and configuring quotas, see Disk Quotas.

- Click the Create button at the bottom of the page to mount and/or record the filesystem. If all goes well, you will be returned to the filesystems list. Otherwise, an error will be displayed explaining what went wrong.

Mounting a local Windows hard disk filesystem

If your system has a Windows partition on one of its hard disks, you can mount it using Webmin so that all the files are easily accessible to Unix users and programs. Windows 95, 98 and ME all use the older vfat format by default, called a Windows 95 filesystem by Webmin. However, Windows NT, 2000 and XP use the more advanced ntfs filesystem format (called Windows NT filesystem) which only a few Linux distributions support.

On the main page of the Disk and Network Filesystems module, select either Windows 95 Filesystem or Windows NT Filesystem from the drop-down box of filesystem types, and click the Add mount button. A form will appear for entering the mount point, source and options.

In the Mounted As field, enter the directory on which you want the filesystem to be mounted. The directory should be either non-existent or empty, as any files that it currently contains will be hidden once the filesystem is mounted.

If you want the filesystem to be mounted at boot time, select Save and mount at boot for the Save Mount option. If you want it to be permanently recorded but not mounted at boot, select Save. Otherwise, select Don’t save if this is to be only a temporary mount.

For the Mount now? option, select Mount if you want the filesystem to be mounted immediately, or Don’t mount if you just want it to be recorded for future mounting at boot time.

For the Windows 95 Filesystem or Windows NT Filesystem field, click on the Disk option and select the partition which has been formatted for your new filesystem. All IDE and SCSI disks, RAID devices and LVM logical volumes will appear in the list. Alternately, you can click on the Other device option and enter the path to the device file for your filesystem, like

/dev/hda2.Select any options that you want to enable. Some useful ones are :

User files are owned by

Because the vfat filesystem format has no concept of users and groups, by default all files in the mounted filesystem will be owned by root. To change this, enter a different Unix username for this option.

Group files are owned by

. Like the previous option, this controls the group ownership of all files in the mounted filesystem.

File permissions mask

The binary inverse in octal of the Unix permissions that you want files in the mounted filesystem to have. For example, entering 007 would make files readable and writeable by their user and group, but totally inaccessible to everyone else. This option is not available for Windows NT filesystems.

Click the Create button at the bottom of the page to mount and/or record the filesystem. If all goes well, you will be returned to the filesystems list. Otherwise, an error will be displayed explaining what went wrong.

Because Windows 95 filesystems have no concept of file ownership and Windows NT filesystems have ownership information that is unsupported by Linux, it is impossible to change the user, group or permissions on files in a mounted filesystem.

Adding virtual memory

As explained in the introduction, virtual memory is used when the processes running on your system need to use more memory than is physically installed. Because not all processes run at the same time, those that are inactive can be safely swapped out to virtual memory and then swapped back in again when they need to run. However, because disks are far slower than RAM, if processes on your system use up too much memory the constant swapping in and out (known as thrashing) will slow the system to a crawl.

Both files in an existing local filesystem and entire partitions can be used for virtual memory. Using a partition is almost always faster, but can be inflexible if you have no free partitions on your hard disk. A system can have more than one virtual memory file or partition, so if you are running out of virtual memory it is easy to add more. The steps for adding additional virtual memory are :

- On the main page of the Disk and Network Filesystems module, select Virtual Memory from the drop-down box of filesystem types, and click the Add mount button. A form will appear for entering the source and other options.

- If you want the virtual memory to be added at boot time, select Save and mount at boot for the Save Mount option. Otherwise, select Don’t save if this is to be only a temporary addition.

- For the Mount now? option, select Mount if you want the virtual memory to be added immediately, or Don’t mount if you just want it to be recorded for future addition at boot time.

- If you want to add an entire partition as virtual memory, select Disk for the Swap File option and select the partition from the list. Otherwise, select Swap File and enter the path that you want to use as virtual memory. If you enter the path to a file that already exists, it will be overwritten when the virtual memory is added.

- Click the Create button at the bottom of the page. If you are adding a swap file which does not exist yet, you will be prompted to enter a size for the file, and Webmin will create it for you. If all goes well, the browser will return to the list of filesystems on the main page.

- Once the new virtual memory has been added, your system’s available memory should increase by the size of the partition or swap file. Use the memory display of the Running Processes module to see how much real and virtual memory is available.

Automounter filesystems

When using Linux, before you can access files on any filesystem it must first be explicitly mounted. This is fine for hard disks that are mounted at boot time, but is not so convenient for removable media like CD-ROMs, floppy disks and zip disks. Having to mount a floppy before you can read or write files on it, and then un-mount it when done is not very user friendly, especially compared to other operating systems like Windows.

Fortunately, there is a solution - the automounter filesystem. This does not contain any files of its own, but automatically creates temporary directories and mounts filesystems when needed. An automounter filesystem mounted at /auto would normally be configured to mount a floppy disk at /auto/floppy as soon as a user tries to cd into that directory. When the floppy’s filesystem is no longer being used, it will be automatically un-mounted so that the floppy can be safely ejected.

Automounter filesystems can be created, viewed and edited in Webmin. Each has a configuration file that specifies which devices it will mount and which subdirectories they will be mounted on. The editing of these configuration files cannot be done within Webmin though - you can only choose which one to use. Most modern Linux distributions come with an automounter filesystem at /auto or /media set up by default, and configured to allow access to floppy and CD-ROM drives.

Another common use for the automounter is to provide easy access to NFS servers. Often an automounter on the /net directory is set up so that accessing the /net/hostname directory will mount all the exported directories from hostname under that directory. This is all done using another automounter configuration file.

Editing or removing an existing filesystem

After mounting a filesystem, you can go back and change the mount directory, source and options at any time. Even most filesystems that were set up as part of your operating system’s installation process can be edited. However, some special filesystem types like proc and devfs cannot be editing though Webmin, as changing them would probably break your system.

The only catch is that filesystems that are currently in use cannot be immediately edited. If any user or process is accessing any file or is in any directory on a filesystem, it is considered busy and cannot be un-mounted and re-mounted by Webmin in order to change it. Because the root filesystem is always in use, making immediate changes to it is impossible. Fortunately, there is an alternative - changing only the permanent record of a filesystem, so that when your system reboots the new options are applied.

The steps to follow for editing a filesystem are:

- From the list of filesystems on the main page, click on the mount point directory in the Mounted as column. A form containing the current settings will appear, as shown below.

- Change any of the settings, including the Mounted As directory, the device or server from which the filesystem is mounted, or the mount options.

- If you want to un-mount the filesystem while still keeping it recorded for future mounting, change the Mount now? option to Unmount. Or if you want to mount a filesystem that is permanently recorded, change the option to Mount.

- Click the Save button to make your changes active. If all goes well, the browser will return to the list of filesystems on the main page. If you are changing a mounted filesystem that is busy, you will be given the option of having your changes applied to the permanent list only. If you are trying to enable quotas on a Linux native filesystem, having the option applied to the permanent list is all that is needed.

To totally remove a filesystem, just edit it and set the Save Mount? option to Don’t save, and the Mount Now? option to Unmount. Assuming it is not in use, it will be un-mounted and removed from the list of recorded filesystems, and so will no longer show up in the list on the module’s main page.

Listing users of a filesystem

If you cannot un-mount or edit a filesystem because it is busy, you may want to kill the processes that are currently using it. To find which processes are using a filesystem, follow these steps:

- From the list of filesystems on the main page, click on the mount point directory in the Mounted as column. The form shown above will appear.

- Click the List Users button in the bottom-right corner of the page. This will display a list of all processes that are reading, writing or in any file or directory in the filesystem.

- To kill them, click the Kill Processes button at the bottom of the page. You should now be able to return to the Disk and Network Filesystems module and un-mount successfully.

Module access control

A Webmin user can be given limited access to this module, so that he can only edit the settings for certain filesystems or only mount and un-mount. Allowing an un-trusted users to mount any filesystem is a bad idea, because he could gain complete control of your system by mounting an NFS or floppy-disk filesystem containing setuid-root programs. However, giving someone the rights to only mount and un-mount certain filesystems that have their options set to prevent the use of setuid programs is quite safe. This can be useful if your system has a floppy or CD-ROM drive and you are not using an automounter.

Once a user has been given access to the module (as explained in Webmin Users, you can limit him to just mounting or un-mounted selected filesystems by following these steps :

- In the Webmin Users module, click on Disk and Network Filesystems next to the user’s name to bring up the access control form.

- Change the Can edit module configuration? field to No to stop him from configuring the module to use a different fstab file or mount commands.

- In the Filesystems that can be edited field, select Under listed directories and enter a list of mount points into the adjacent text box. For example, you might enter /mnt/floppy /mnt/cdrom. It is also possible to enter a directory like /mnt to allow access to all filesystems under it.

- Change the Can add new filesystems? field to No.

- Change the Only allow mounting and unmounting? field to Yes, so that the user cannot actually edit filesystem details.

- Hit the Save button to activate the new restrictions.

On Linux systems, the Allow users to mount this filesystem? field can be used to allow the use of the command-line mount and unmount programs. Other tools like the Gnome mount panel applet and Usermin also make use of this feature, which may be a better way to give normal users mount and un-mount privileges.

Configuring the Disk and Network Filesystems module

Like other modules, this one has a few options that you can change. To see them, click on the Module Config link in the top-left corner of the main page. This will take you to the standard configuration editing page.

A comparison of filesystem types

Unlike other operating systems, Linux supports several different types of filesystems that fully support Unix file permissions and ownership information. Originally the ext2 (called the Old Linux Native Filesystem) was the only choice, but newer kernel versions and distributions have added support for ext3, ext4, reiserfs and xfs. This section explains the benefits of each of these alternative filesystem types.

New Linux Native Filesystem (ext4)

The

ext4file system is a successor to theext3file system. Compared to theext3file system, theext4file system increases some of the size limits and provides some improved performance characteristics.Linux Native Filesystem (ext3)

Very similar to

ext2, but with support for journaling. This means that if your system crashes or loses power without having a chance to properly un-mount its filesystems, there is no need for a lengthy fsck check of the entireext3filesystem as would be needed withext2. Becauseext3filesystems are so similar toext2, they are stored on disk in almost exactly the same format. This means that it is relatively simple to convert an existing filesystem to ext3 by creating a special journal file.SGI Filesystem (xfs)

XFS was originally developed by SGI for its Irix operating system. It supports journaling and includes native support for ACLs and file attribute lists. The ACL (access control list) support in particular is very useful, because it allows you to grant access to files in ways that would be impossible with the normal Unix user/group permissions. XFS supports large files and large file systems.

Rieser Filesystem (reiserfs)

ReiserFS is a totally new filesystem designed to be faster and more efficient than

ext2. It supports journaling likeext3does, and deals much better with large numbers of small files than other filesystems. However, it is probably not as mature asext3orxfs, and does not support quotas.

To see which of these filesystem types are supported by your system, go into the Partitions on Local Disks module and select an unused partition of type Linux. At the bottom of the page will be a form that you can use to create a new filesystem on the partition in one of the types that is available on your system. Most new Linux distributions will support ext4, some will also support xfs and reiserfs.

Linux also supports several older filesystem types such as ext, xiafs and minix. You will never need to use these unless you have an old disk formatted with one of them.

Other operating systems

The Disk and Network Filesystems module supports several other operating systems in addition to Linux, using basically the same user interface. The main differences lie in the filesystem types support by each operating system, and the type used for hard disk Unix filesystems. Only Linux, Solaris and Irix display a drop-down menu of available partitions when adding a hard disk filesystem - on other systems, you must enter the IDE or SCSI controller and drive numbers manually.

The operating systems on which the module can be used, and the major differences between each of them and Linux are:

Sun Solaris

Solaris uses

ufs(called the Solaris Unix Filesystem by Webmin) as its standard filesystem type for local hard disks. It has many of the same options asext3on Linux, but does not support group quotas, only user. Adding virtual memory is also supported, in exactly the same way as on Linux. The NFS filesystem type on Solaris is also similar to Linux, but supports mounting from multiple NFS servers in case one goes down. When entering servers into the Multiple NFS Servers field, they must be comma-separated likehost1:/path,host2:/path,host3:/path. Solaris systems can only mount Windows Networking Filesystems if the rumba program has been installed. However, they can only be mounted temporarily, not recorded for mounting at boot time. One interesting filesystem type that only Solaris supports is the RAM Disk, i.e.tmpfs. Files in a filesystem of this type are not stored on disk anywhere, and so will be lost when the system is rebooted or the filesystem is un-mounted. By default, Solaris usestmpfsfor the/tmpdirectory.FreeBSD

FreeBSD also uses

ufsas its standard local hard disk filesystem type, although it is called the FreeBSD Unix Filesystem by Webmin. It has most of the same options as Linux, and supports user and group quotas. Virtual memory is also supported on FreeBSD, but with the catch that once added it cannot be removed without rebooting. NFS is supported with similar options to Linux, but Windows networking filesystems are not.OpenBSD

OpenBSD uses the

ffsfilesystem type for local hard disk, which is called the OpenBSD Unix Filesystem by Webmin. Like FreeBSD, it supports virtual memory and NFS but not Windows networking filesystems.HP/UX

HP’s Unix variant uses

hfs(HP Unix Filesystem) as its standard local hard disk filesystem type, but also supports the superior journalledvxfs, called HP Journaled Unix Filesystem by Webmin. Both have an option for disk quotas, but for users only. Virtual memory is supported and can be added and removed at any time, but is always mounted at boot if permanently recorded. NFS is also available, with similar options to Linux, but there is no Windows networking filesystem type.SGI Irix

Newer versions of Irix use

xfs(SGI Filesystem) as their standard hard disk filesystem type, which supports all the same options asxfson Linux, including user quotas, ACLs and file attributes. Theefs(Old SGI Filesystem) type is also available but should only be used if you have old partitions that are already formatted for it, or are running an old version of Irix. Irix supports NFS with similar options to Linux, but not Windows networking. AppleTalk and Netware filesystems can also be mounted using command-line tools, but are not yet mountable or editing from within Webmin. The operating system also has standard virtual memory support, but with the peculiarity that the first swap partition on the first hard drive is always added as virtual memory automatically using the special/dev/swapdevice file.SCO UnixWare

UnixWare has very similar filesystem support to Solaris, but also adds support for the hard disk based

vxfs(Veritas Filesystem) type.

If your operating system is not on the list above, then it is not supported by the Disk and Network Filesystems module. In some cases this is because the code has not been written yet, such as with AIX or Tru64/OSF1. MacOS X on the other hand mounts all hard disk partitions at boot time, and automatically mounts network filesystems when requested by the user through the GUI. Therefore it has no need for a Webmin module for managing filesystems.